NOTE: AN IMAGE USED UNDER FAIR-USE NON-COMMERCIAL COMMENTARY HAS BEEN REMOVED DUE TO A TAKE-DOWN NOTICE. WHATEVER. IT’S BEEN AGES.

Thirty-some odd years ago, as my political sensibilities began to awaken, one of my biggest questions was why Richard Nixon was, in the first place, allowed to resign, and, even worse, why he was pardoned. Wasn’t the whole point of the Revolution making sure no person, and especially the nominal leader, is above the law? That’s why we did the whole “there-shall-be-no-kings” thing, right? Shouldn’t Nixon have been sent to prison to send a message that our country does not tolerate that sort of behavior? After all, he’s just a citizen who happens to be President.

Right?

I was a naive pre-teen.

***

Craggy, green, grey, brown, blue, and beautiful, Washington’s Puget Sound flows from the Pacific Ocean at Deception Pass, down into Seattle, saying hello to Tacoma on the East, and Gig Harbor on the West, before cradling Olympia at its base. Gig Harbor and Tacoma are separated by a roughly mile-wide channel called the Tacoma Narrows.

By the late 19th century, Tacoma was chosen as the terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and had developed into a substantial port city. Getting goods from Tacoma across Puget Sound into the Olympic peninsula required miles and miles of road travel (more than 100) of first, wagons, and then trucks driving southwest into Olympia and then northward into the peninsula. What could make more sense than building a bridge across a (relatively) narrow portion of the Sound?

After decades of discussion and debate, military interests–as they do–finally sealed the deal, and construction began on the (first) Tacoma Narrows Bridge in November of 1938. 18 Months later, on July 1, 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge officially opens. At the time of its opening, it was the third-longest suspension bridge in the world, covering 5,959 feet, but barely 39 feet wide. 7,000 people showed up for the opening, and the bridge–featuring modern and Art Deco flourishes–was widely considered quite beautiful.

There was much rejoicing.

Richard M. Nixon first ran for President in 1960, famously losing to John F. Kennedy. For the next eight years, during which time Kennedy was assassinated and Lyndon B. Johnson got the United States fully into the Vietnam War, Nixon worked to promote conservative causes. After LBJ declared he would not seek reelection in 1968, Nixon took advantage of the chaos facing the Democrats (Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in June of 1968, and Hubert Humphrey emerged from the violence-plagued Democratic National Convention with the nomination). Campaigning with Spiro Agnew, Nixon mined the Forgotten Man and Silent Majority playbook to offer an alternative to the countercultural revolutions facing the country. He also allowed the media to argue that he had a secret plan to end the Vietnam war. (The United States wouldn’t leave the war until 1975.)

Nixon garnered a healthy 301 electoral votes to Humphrey’s 191 and George Wallace’s 46. (Wait? Where’d he come from? Eh–he’s not central to this story.) Despite the healthy electoral college margin, the popular vote margin was much closer: only 500,000 votes separated Nixon and Humphrey.

On January 20, 1969, Nixon took the oath of office, and pledged to turn partisan politics into a new age of unity, urging Americans to learn from one another rather than shouting at one another.

And for the first 800 some-odd days of his Presidency, Nixon enjoyed approval ratings which were, while not stellar, consistently above 50%. In April of 1971, around the time Nixon installed a secret recording device in the Oval Office (only a handful of people knew it existed at the time), Nixon’s ratings took an unrelated detour to visit the Trump basement. By the time the 1972 election rolled around, however, his opponent was the hapless George McGovern, and Nixon won all but 18 of the electoral votes, easily getting reelected in one of the largest electoral blowouts in history. Only FDR in 1936 and Ronald Reagan in 1984 had more electoral votes.

The popular vote margin was a staggering 18 million. With such popular support, it is unsurprising that Nixon was sitting on a higher than 65% approval rating at his second inauguration on January 20, 1973. More surprising, however, with such a blowout, the House of Representatives and the Senate were both healthily dominated by Democrats.

***

At its opening, it was clear that the Tacoma Narrows Bridge would bounce, even in wind as low as 4 miles an hour. For the next three months, motorists would experience routine waves in the roadway of 1 to 5 feet (rising and falling 2 to 10 feet) and occasionally extreme waves of 10 feet (rising and falling 20 feet). Cars would lose traction on the roadway, and drivers even experienced seasickness.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge quickly earned the nickname “Galloping Gertie” and by September of 1940, just 3 months after it opened, engineers knew they had a very big problem.

***

On June 17 of 1972, five men broke into the Democratic National Committee’s offices at the Watergate office building in Washington, D.C. And were promptly arrested. This invasion was actually the second time Watergate schemers had broken into the offices. Earlier, on May 28, 1972, the team of burglars had entered the offices to photograph documents and to tap phones. They were apparently unsuccessful with one of the phone taps, so they returned on June 17 to finish the job.

Initial efforts by Nixon to cover up the burglary were largely successful. The media even ran stories sympathetic to Nixon having to deal with all the distraction. By January 30, 1973, each of the burglars had been convicted (whether by jury or by pleading guilty), and the issue probably could have ended there.

It didn’t, though, because there were tremors. Sources in the government, namely “Deep Throat” (FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt), kept feeding information to the media from June 1972 through the end of the burglars’ trials. In addition, one of the burglars wrote a note to District Judge Sirica that there was a high-level coverup.

There was just enough information floating around to get the Senate to establish a committee to investigate the Watergate break-in on February 7, 1973. Beginning on May 17, 1973, and running through August 7, 1973, wall-to-wall televised hearings were held. The real bombshells of that era involved the testimony of White House assistant Alexander Butterfield in July of 1973, who acknowledged that Nixon had installed a recording system in the Oval Office. Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox subpoenaed the tapes, and Nixon refused to release them.

***

The engineers studying Galloping Gertie knew the bridge trembled significantly before it even opened to the public. They tried stabilizing the road deck with additional cables. The cables snapped soon after they were installed. They tried installing additional cable stays. They did almost nothing. They installed hydraulic buffers between the towers and the deck, which were intended to limit the up-and-down motion. Due to damage during installation, however, they never went into service. Wind deflectors were envisioned, but never had the chance to be installed.

Just barely more than four months into service, on November 7, 1940, a stiff 38 mph wind blows across the bridge at 7:30a. By 9:30a, the wind has increased to 42 mph, and the bridge undulates with waves 2-5 feet high.

33 minutes later, at 10:03a, the roadway begins to twist laterally and in just 4 minutes, the road twists at 45-degree angles with each side of the road taking turns lurching 28 feet–nearly 3 stories–into the air.

At 10:30a, a chunk of concrete falls into the Sound, and at 11:02a, a 600-foot long section breaks off.

By 11:08a, the final section of roadway falls into the Narrows.

***

Bubbling under the surface of the Watergate investigation was the realization by the investigators that Nixon was overwhelmingly corrupt and he had to go. But bringing him down would be incredibly difficult.

In early 1973, Nixon’s approval rating, while not stellar, was still better than 50%. It wasn’t until the secret recording system was publicized that his approval dipped into, and sank below, Trump territory. Even then, at that time, only about 25% of the country favored impeachment and removal.

The Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, added another layer of complexity because he was just as–if not more–corrupt than Nixon. Getting rid of Nixon meant Agnew would become President, which was unacceptable to the investigators. Given the conceptual impossibility of successfully impeaching and removing Nixon, how much political capital would it take to get rid of both? Was there enough in the world?

The fantastic MSNBC podcast series “Bagman” details how Agnew was forced to resign, but resign he did on October 10, 1973, after accepting a plea deal for tax evasion. He only told Nixon of his impending resignation the night before.

Meanwhile, and in defiance of Presidential orders, Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox refused to abandon his subpoena for the Watergate tapes. On October 20, 1973, 16 months after the break-in at the Watergate office building and 10 days after his Vice-President was forced to resign, Nixon ordered Attorney General Richardson to fire Archibald Cox.

Richardson refused and resigned in protest.

Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus was then ordered by Nixon to fire Archibald Cox.

Ruckelshaus, too, refused and resigned in protest.

Nixon finally stumbled on Solicitor General Robert Bork, who–superhero that he was–carried out the order. The “Saturday Night Massacre” was complete.

It was not, however, the end of Nixon’s presidency.

A new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, would be appointed, and the investigation continued. Gerald Ford ascended to the Vice-Presidency in December of 1973. Nixon’s approval rating was only a little above 25%, but, still, only 30% of the country favored impeachment and removal.

On March 1, 1974, a grand jury indicted seven former Nixon aides, and secretly named Nixon an unindicted coconspirator. For the next five months, the House of Representatives prepared articles of impeachment. There were three articles of impeachment prepared: obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. They never received a vote.

Finally, on August 5, 1974, the recording of a conversation between Nixon and his aide Haldeman made on June 23, 1972 was released. It clearly showed Nixon trying to keep the FBI from looking into the Watergate break-in. Nixon’s previous denials of having any involvement in the scandal were finally dead and buried. Far from being a victim of a witch-hunt, it was clear he was at the center of a vast cover-up.

Two days later, Nixon was visited by Senators Barry Goldwater and Hugh Scott, and Congressman John Jacob Rhodes. Nixon was informed that he had no realistic chance to survive impeachment and removal.

***

It was clear from the very short period the Tacoma Narrows Bridge was open that it would be a boon for both the military and the civilian population. So the bridge would have to be replaced. A repeat of the bridge’s fate, however, was unacceptable, and Galloping Gertie’s collapse was studied, and restudied, and studied some more over the next few years. (The nation’s attention was also focused elsewhere for four or five years there in the middle part of the decade, too.)

The design of the replacement bridge took place largely in the laboratory, with over 200 configurations mocked up and subjected to wind tunnel testing for more than a year. Finally, the designers settled on new innovative approaches to constructing the bridge, and the new Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which would eventually come to be known as Sturdy Gertie, opened on October 14, 1950. Due to the designers learning from their catastrophe, and implementing new designs, this bridge remains one of the longest, and safest, suspension bridges in the United States.

***

Just as the pressure was becoming relentless, and just as the limits were going to be exceeding and everything was going to crater around him …

Nixon was given an escape hatch.

He was not going to become the first President impeached and removed. A giant damper was placed under the White House, and the external tremors stopped.

Crowing about a witch-hunt all the way, Nixon resigned from the Presidency on August 9, 1974. The night before, Nixon addressed the nation, never once apologizing for his conduct. In 2007, Conrad Black, recently pardoned by President Trump because he wrote a nice book about him, wrote that Nixon turned what was supposed to be a humiliating event into “a virtual parliamentary acknowledgement of almost blameless insufficiency of legislative support to continue.” In other words, Nixon deftly got away with it, grumbling “haters” on the way out the door.

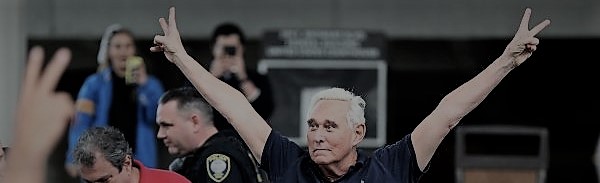

Half an hour from when Nixon entered his helicopter raising his arms in a Vee, flashing the peace sign, Gerald Ford was sworn in as President. President Ford then took to the lectern to say, among other things, “My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.” He also said “Our Constitution works; our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule.”

A month later, he granted Nixon a full pardon.

Nixon spent the next 20 years trying to ingratiate himself back into society, eventually earning millions of dollars and having Presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton present at his funeral.

***

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge’s spectacular collapse has long been considered a textbook example of how resonance can destroy something large with small, regular impulses matching the structure’s natural frequency. According to the textbooks, the bridge had a natural frequency, and as gusts of wind hit the bridge, it oscillated at greater and greater amplitudes. The physics of the collapse are probably better seen as something else–vortex waves, torsional forces, and flutter all played significant roles–but the lesson is the same: A very small input, repeating over time, can lead to catastrophic collapse.

The bridge’s collapse, though spectacular and staggering, led to a greater understanding of bridge design which would make future bridges safer, more reliable, and far less susceptible to self-destruction.

***

The first article of impeachment against Richard Nixon alleged obstruction of justice. The House outlined nine means by which Nixon carried out his obstruction, including:

3. approving, condoning, acquiescing in, and counselling witnesses with respect to the giving of false or misleading statements to lawfully authorized investigative officers and employees of the United States or misleading testimony in duly instituted judicial and congressional proceedings;

4. interfering or endeavoring to interfere with the conduct of investigations by” the DOJ, the FBI, and other agencies; “

5. approving, condoning, and acquiescing in, the surreptitious payment of substantial sums of money for the purpose of obtaining the silence or influencing the testimony of witnesses, potential witnesses or individuals who participated in such unlawful entry and other illegal activities;

8. making or causing to be made false or misleading public statements for the purpose of deceiving the people of the United States into believing that a thorough and complete investigation had been conducted with respect to allegations of misconduct on the part of personnel of the executive branch of the United States … and that there was no involvement of such personnel in such misconduct: or

9. endeavouring to cause prospective defendants, and individuals duly tried and convicted, to expect favoured treatment and consideration in return for their silence or false testimony, or rewarding individuals for their silence or false testimony.

The second article of impeachment alleged abuse of power by engaging in conduct that violated the constitutional rights of citizens, impaired the due and proper administration of justice and the conduct of lawful inquiries, or contravening the laws governing agencies of the executive branch and the purposes of these agencies. The abusive conduct unfolded in five ways, including:

2. misusing the FBI and other investigative agencies to conduct investigations for purposes unrelated to national security; and

5. knowingly misusing the executive power by interfering with agencies of the executive branch, including the FBI.

The third article of impeachment alleged contempt of Congress by failing, without lawful cause or excuse, to produce papers and things as directed by duly authorized subpoenas.

***

I suppose it’s a testament to the bonkers politics of the Nixon era that engineering the resignation of not just the President but also the Vice-President was seen as the palatable alternative to impeachment and removal followed by prosecution. Nothing says “respect for the rule of law and the orderly process of governance” like secretive backroom negotiating.

My folks, who lived through the whole Nixon fiasco, have consistently reassured me that, yes, it was probably wrong to let Nixon off easy. But. The country was a disaster. The Vietnam war was a disaster. Civil unrest was a disaster. Everything sucked. The country would fall apart if Nixon was pulled from office and thrown in prison. It was the only solution to a very bad situation. The turmoil had to stop. And my folks aren’t the only ones who have said that everything would fall apart if impeachment had gone forward and then the Senate had removed a President from power.

But I am now a jaded and cynical middle-aged man. And I am convinced that the 1970s resignations of first, the Vice-President, and then the President, followed by the full and absolute pardon of Nixon, set in motion the paralyzing conditions that currently face the United States. A massively unpopular, criminal, and corrupt President–whose acts are in many ways worse than the acts detailed in the Nixon articles of impeachment–leads the country deeper into filth during a time when the tremors haven’t yet metastasized to total chaos. Authoritarianism isn’t quite here yet, but it is a mere breath away.

And there is absolutely no recourse or political courage to do anything about it.

Failure to impeach and remove Nixon was a missed opportunity to establish respect for the rule of law and to show that the Constitution and the Republic is designed to hold corrupt and abusive Presidents fully accountable. Ford was wrong. Nixon’s resignation, followed by a pardon, was anything but the demonstration that the rule of law controls.

The country learned no beneficial lessons by letting Nixon avoid impeachment, didn’t learn any lessons that exceeding design limits means guaranteed personal destruction.

Instead, the country learned that the worst mistake a President can make is to resign.