In my previous post, I dove into the way the drafters envisioned the composition of the Legislative and Executive branches, and how the populace was supposed to be kept at a distance from the Executive and the Senate. This post takes a look at Amendment XII and Amendment XVII.

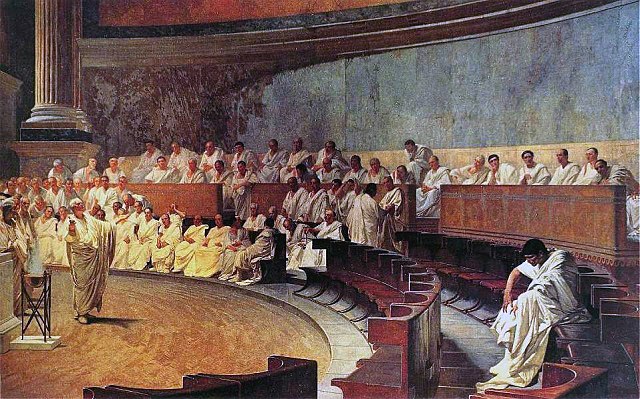

Utopian Ideals

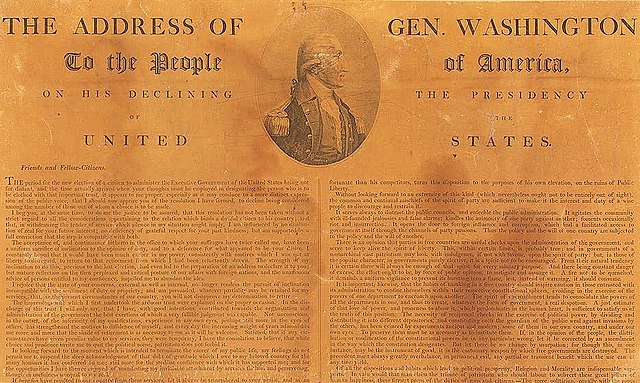

I also alluded to the fact that this framework didn’t last long. After Washington decided to step down from the Presidency, the election of 1796 presented a new challenge to the young nation. The Utopian dream of the Electoral College failed to put any guardrails on the way Electors were chosen by each state. As I mentioned last time, it appears the drafters assumed that Electors would be appointed by the legislatures of each state, much in the same way Senators were appointed. It isn’t explicit, but such thinking is consistent with the efforts the drafters made to remove popular impulse from the composition of the Executive branch. That’s not how it worked in practice, though, with some states appointing Electors, some states having Electors run for election, and some states doing some hybrid approach.

Tied to this failure to erect a framework for Electoral vote consistency, the drafters also failed entirely to accept the reality that consolidated political factions would arise. Writing in Federalist No. 68, Hamilton foresaw partisan electioneering, but pretended that Americans—famous for freaking out and overthrowing a monarch over the price of tea—would be level-headed:

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. … [The drafters] have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office. … Thus without corrupting the body of the people, the immediate agents in the election will at least enter upon the task free from any sinister bias. Their transient existence, and their detached situation, already taken notice of, afford a satisfactory prospect of their continuing so, to the conclusion of it. The business of corruption, when it is to embrace so considerable a number of men, requires time as well as means. Nor would it be found easy suddenly to embark them, dispersed as they would be over thirteen States, in any combinations founded upon motives, which though they could not properly be denominated corrupt, might yet be of a nature to mislead them from their duty.

Hamilton used a ton of ink just to say “our better angels will do a good job, and we won’t coordinate our votes.”

So. About that.

Political Factions

Political factions were not unheard of to the Americans. The Whigs and Tories battled each other in the British Parliament throughout the 18th century, so the drafters quite aware that legislative bodies tended to consolidate in various manners. Even while drafting the Constitution, the drafters were aware that there were Federalists—who wanted the Constitution to be enacted—and anti-Federalists who were skeptical. The notion, then, that Americans would somehow avoid banding together in political parties was quite naïve.

The Election of 1796

And that naiveite first presented a problem in 1796. John Adams (as a Federalist) and Thomas Jefferson (as a Democratic-Republican) were put up for the Presidency, with each candidate’s surrogates rhetorically savaging the other. While most electors would vote for the primary candidate (in this case, Adams or Jefferson) and another member of the faction also for President (say, Thomas Pinckney or Aaron Burr), a handful of Electors split their votes across the parties—one even cast his lot for Washington, even though Washington had just finished telling everyone he wanted to go home to Mount Vernon.

The result was a convoluted mess with John Adams earning the necessary 71 electoral votes for victory, and Thomas Jefferson gaining 68. This presented a problem, though, since they were of different parties.

The Election of 1800

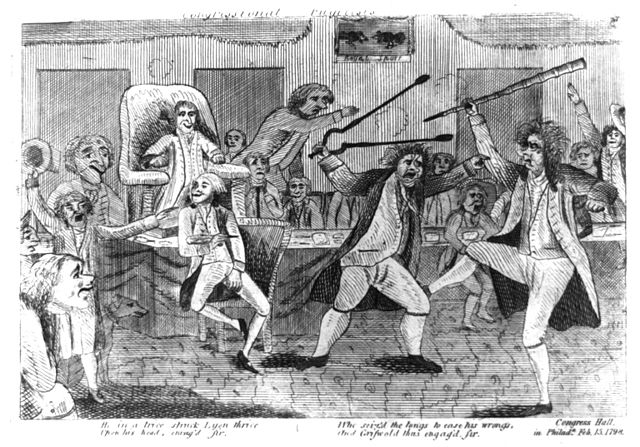

By 1800, factionalism was well in place, and despite assurances that the American system would never, ever, ever lead to “preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with to prostitute their votes,” both the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans began caucusing to choose candidates to be the choice for President.

The Election of 1800 formally pitted Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr against John Adams and Charles Pinckney. When it was all said and done, with Adams’ popularity waning (with no little thanks to Hamilton doing his best to blow him up), Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr both ended up with 73 votes each.

Oops. Each had a majority.

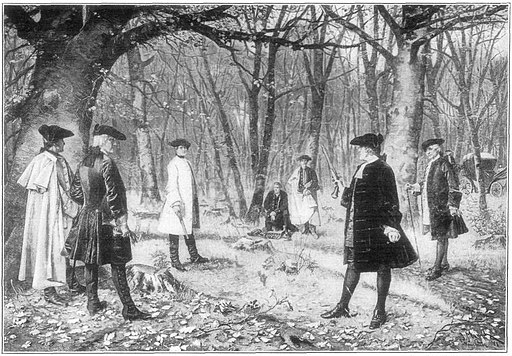

The election was taken up by the House of Representatives, and, even though he was thought of as Jefferson’s running mate, Burr refused to accede to that agreement. Which led to Hamilton doing his best to get the Federalists in the House to vote for Jefferson, who Hamilton also wasn’t fond of, but liked more than Burr. Jefferson became President. Burr would kill Hamilton in a duel in 1804.

Ah….History!

The Twelfth Amendment

In the wake of those bizarre hijinks during the 1796 and 1800 elections, Congress passed the 12th Amendment in 1803, and it was ratified in 1804. The 12th Amendment changed the way Electoral votes were tabulated. Rather than one slate of candidates being sent to Congress, with the runner-up becoming Vice-President, now two distinct slates—one for President, and one for Vice-President—were sent to Congress.

It was a small change, but a crucial one. A scant 16 years or so after the unique experiment envisioned by the Constitution began, where unencumbered wise men chose other unencumbered wise men to head the state, the experiment was essentially over. From that point on, political parties dominated, Presidential campaigns became a thing, and states began apportioning Electors based on popular vote, often with winner-take-all frameworks.

Rather than keeping the populace at a distance, and removing the President from the concerns of needing to please a core set of voters, the 12th Amendment paved the way for the Executive to be beholden to his base, to “sacrifice his duty to his complaisance for those whose favor was necessary to the duration of his official consequence.”

The Electoral College Is Pointless

By failing to erect guardrails against campaigning, by failing to preserve the wall between the populace and the Presidency, the Electoral College becomes pointless. If, over the course of decades, the populace is given more and more of a say in who is to be President, the essential nature of the Constitutional President becomes corrupted.

If the popular vote is to form a basis for who will be President, the Electoral College is unnecessary, and the continued existence of it simply leads to lack of participation in elections and inequities. For the former, one needs only to look at voters in California or Texas who see no point in voting because the states are guaranteed to go either Blue or Red. This is tied to the winner-take-all policies of most states where the popular vote winner in that state receives all Electoral votes, even if the margin of victory is a fraction of a percent. This allows a President to focus on a particular sort of base, identify that base in particular states, and ignore the rest of the population. It is, essentially, a form of gerrymandering on a national scale.

If the Constitution envisioned an Executive branch that was tasked with running his branch of government with a populace that had only a limited emotional connection to whoever was in office, that is no longer the case.

The 17th Amendment

The other seemingly minor change to the Constitution involved the way Senators are seated. Whereas they were originally appointed by the State, the 17th Amendment—passed by Congress in 1912 and ratified in 1913—changed that. Since the passage of the 17th Amendment, Senators are directly elected by the People.

The issue was present during the drafting of the Constitution, but only one delegate to the Constitutional Convention, James Wilson, favored direct election of Senators. But the issue kept cropping up throughout the 19th century. Over that century, there were three main arguments proffered for altering the way Senators are chosen: corruption, electoral deadlock, and populism.

While there may have been concerns that Senate hopefuls were paying off their state legislatures to get named to the position, and there were certainly times when some states failed to send their Senators to Congress in a timely fashion, it really seems that populism was the driving force to making the Senate accountable directly to the people. At least, that’s the theory behind direct elections. Being held accountable directly to the people, though, means, for better or worse, kowtowing to interests.

Whatever the impetus for amending the Constitution (and there are arguments to this day whether the 17th Amendment should be repealed) it’s clear that it represented a shift in the nature of the body. Whereas the Senate was supposed to be an august institution filled with the best of society, now any old riff-raff like Rand Paul or Ted Cruz can become Senator. And Senators wield enormous power if they want to.

Likewise, they can fail to wield power, which also has enormous implications. That’s the subject of my next post, which looks at our current crisis of leadership.