This post is the third installment of my short look at the Constitution and how democracy is intetionally and unintentionally stymied under its construction. The first post looked at the theoretical underpinnings which were meant to justify the whole silly thing. The second post looked at how the system was abandoned less than two decades after it began with the 12th Amendment. I also touched on the 17th Amendment’s change in how the Senate is seated. In this post, I look at how the electoral college doesn’t reflect democracy. The Senate’s role in creating bad governance will be addressed in my next and final post in this series.

Democracy Isn’t Required

As a starting notion, it’s valuable to remember that democracy isn’t the only system out there, and indeed, direct democracy was originally limited in the Constitution. A population can be governed by a person that was not directly elected. Billions of people are born into, live in, and die in systems of government in which the populace has no voice in who rules them. Just as a K-12 student cannot control her principal or superintended–yet must still follow school rules and codes–and just as an Apple employee has no say in who is her CEO, even we in nominally democratic societies are familiar with subsuming ourselves to policies promulgated without our input.

Of course, we–as practitioners of democracy–tend to favor democracy. And sure, the people in these alternative systems might not be pleased about their lack of input. Without meaningful ways to assert their self-control, or even without the penury that leads to revolt, civilizations have muddled through, if not have done just fine in isolated undemocratic systems across history. Entropy is powerful and explains how an Apple employee displeased with Tim Cook, or a seventh-grader irritated with the Superintendent, will nonetheless go about her business with relative indifference because she has very little to say about it. It wasn’t her decision to put these people in charge anyway, and the Boards might sour on them and remove them if they don’t do a good job steering the mission.

That’s more or less how the Constitution saw the Executive branch’s interaction with the Legislature.

Giving People Democracy

If, however, a glimmer of democracy enters the equation, the dynamic changes. Suddenly, the person leading a venture becomes very important.

If the employees of Apple can vote for their CEO–and Tim Cook won the majority of employee votes–that Tim Cook-hating Employee will likely still be unhappy. She’d know that she’s in the minority, however, and–especially if Cook won the election by a large popular margin–she just has to deal with it.

The worst possible situation for that employee, however, is when she’s allowed to vote for CEO, and her choice is also the majority’s choice, but some stupid voting mechanism means that the votes coming from North Dakota carry twice the weight of her vote in Seattle, causing the loser of the popular vote to become CEO. Minority rule can lead to dissension.

Sometimes a venture can weather minority rule. If a school is given the option of having cheeseburgers or pizza for lunch, and the majority vote for pizza, but the principals say, “right, so cheeseburgers it is!” there probably isn’t going to be a lot of grumbling. Almost everyone likes both cheeseburgers and pizza.

If, however, the choice is between pizza and frog legs, and the majority votes for pizza but are forced to accept fried frog legs as the meal, there’s going to be some disgusted, pissed off kids. Sure, frog legs are fine. I’ve had them. They taste like chicken. They’re still not something I would vote for over pizza.

The Electoral College Disrupts Democracy

Over the course of the American experiment, the electoral college has created a situation where the loser of the popular vote has become President five times, twice in just the past two decades: John Quincy Adams in 1824, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, George W. Bush in 2000, and Donald Trump in 2016. None of these Presidents have been considered great, and only John Quincy Adams has been considered better than middling.

Unpopular candidates can become President because individual states, free from Constitutional guardrails, apportion their electoral votes how they see fit. The overwhelming majority of states choose to apportion votes on a winner-take-all basis; only Maine and Nebraska apportion votes. That means in every other state, the person who has the slightest majority of votes gets every single electoral vote in that state. In large states, like Texas and California, that leads to gobs of votes going one way or another. (“Faithless” electors—one might call them Constitutional electors—are a thing, as I mentioned earlier, but they have thus far been irrelevant in recent history.) It also leads to low voter participation, as I touched on in a post back in September.

The 2016 Election

To get a feel for how this works, let’s take a look at the 2016 election (told you in September I’d get back to this!), which presents the most recent, and perhaps most glaring, discrepancy. (Samuel Tilden in 1876 might have a beef with that. He is the only popular vote winner to lose the electoral vote despite having an outright majority of votes. All other similarly situated popular vote winners merely had a plurality of votes.)

Hillary Clinton received 65,794,399 votes for President, while Donald Trump received 62,955,202, a difference of 2,838,197, or a 1.04:1 ratio. That’s more people than are in Wyoming, Vermont, the District of Columbia, and Alaska combined.

And yet Trump received 304 electoral votes to Clinton’s 227. (Remember the faithless electors? That’s why it doesn’t add up to 538.) That’s a 1.33:1 ratio the other way.

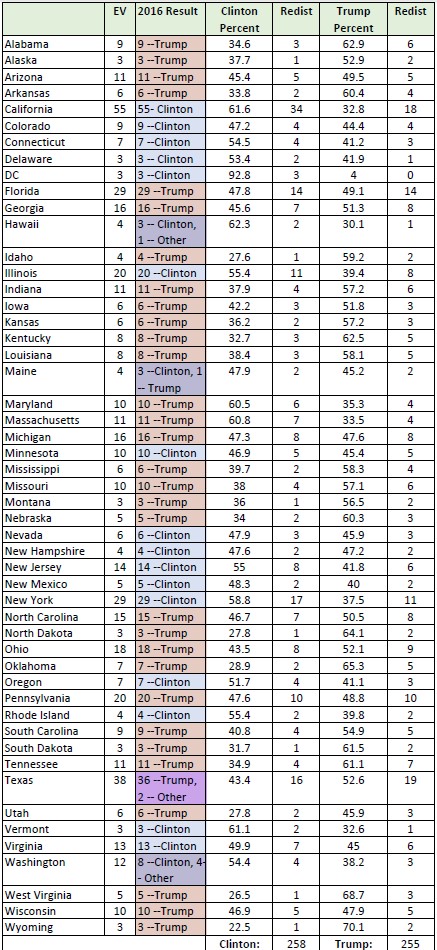

If each state apportioned electoral votes based on the popular vote in each state, however, the result would have been much more similar to the popular vote breakdown:

Interestingly, the ratio between Clinton’s electoral tally and Trump’s tally is only 1.01:1, which is slightly worse than her popular vote ratio. Moreover, neither candidate would have reached the required 270—in my rundown, I’m simply assigning the 25 unallocated electoral votes to a generic third party or parties. The vote then would have gone to the gerrymandered and Republican-controlled House of Representatives, who would have almost assuredly chosen Trump as the victor. That is, unless they chose to dodge the bullet of installing a wrecking ball, a dubious supposition.

Even in 2016, then, populace participation in democracy would have been stymied by an inherently undemocratic framework.

(Fun fact: even though there will be more Democratic Representatives in the House than Republicans, if the 2020 Presidential election ends up going to the House, the Republicans will have an advantage. This is because each state gets one Representative, and there are more small states with Republican control than there are states with Democratic control!)

It is one thing entirely to have an undemocratic policy enshrined in the Constitution, but to steadfastly enforce that undemocratic policy throughout the nation’s history so that a populace does not ever get a whiff of direct democratic input into the workings of the Executive. It is altogether a different thing when you tell a populace that it has a say in the matter, but then take it away through convoluted vote apportionment intended to give outsized importance to sparsely populated areas.

A Dinner of Boiled Frog Legs

It is no surprise that Trump’s approval rating has barely even sniffed the 50% approval mark (except for in Rasmussen polls–which, c’mon, it’s Rasmussen—and for about 4 days after his inauguration).

Had the two candidates presented a choice between pizza and cheeseburgers, the outrage would have died down after a few months. For example, one month after taking office, George W. Bush enjoyed a 51% approval rating, even though he received fewer popular votes than Al Gore. (After 9/11, Bush’s approval rating soared to 80+%, and he coasted in positive territory just until the beginning of his second term, where he continued to plummet until eventually leaving office in the mid-20s.) That early-term buoyancy can be attributed to the superficial comparison that Bush and Gore were similar politicians—Gore was a boring and wonky centrist who looked to the left, and Bush was an affable but somewhat idiotic centrist who looked further to the right. Pizza and cheeseburger on the surface.

For sure, Democrats despised Bush, for reasons, and desperately wanted to defeat him in 2004. And they rightly pointed to the plethora of civil liberties abuses which occurred under the Bush Administration, the covertly racist dogwhistles, and the nascent fascism. Those concerns are more esoteric to a populace that really doesn’t have time to follow every little offense, especially when the nation is terrified. Democrats failed to make a compelling argument for unseating him in 2004, and he continued on as President.

The choice in 2016, however, was far different for Democrats, however. Running very much as a Gore-esque centrist forced into looking perhaps a little more leftward, Clinton appeared to present herself as a slice of—if not supreme—at least cheese pizza. Trump, however, was assuredly boiled, not even fried, frog legs. Cheese pizza won the popularity contest, by a lot of votes, but the nation got frog legs. And, bizarrely, is expected to be happy about it.

The country obviously isn’t happy about it, for many good reasons, and only part of the discontent is due to the ridiculous Electoral College.

The other reason is the Senate, and my next post will talk a little about why Trump is boiled frog legs, and why the Senate poses an impediment to doing anything about his abuses.